molekylgallery

Malmö Fotobiennal 2017 10.6 - 19.6

The society of the spectacle ULF LUNDIN "5 - 9" ZHOU HANSHUN "FRENETIC CITY"

Ulf Lundin "5-9" www.ulflundin.nu

Sweden is at work. In the winter it gets dark by four, just as the luckiest souls can leave the office. Some remain behind. Shafts of light soar towards a black sky. What goes on in these stranded spaceships? What kind of life vibrates in the myriad of gleaming windows?

At a distance it looks beautiful. An unfathomable conglomeration of life stories, far too vast for us to comprehend even a fraction. We zoom in. A man is lecturing in the conference room. He gestures and looks serious. Perhaps he is nervous. Perhaps he is imagining that a boss or other important person is scrutinising him. He must be imagining something. Because he’s alone. The conference room is empty. Next to him, in a parallel universe, two men are sitting staring at huge screens. The blue light shines on them. They are in another world. Higher up, a person is detained by a mobile phone. And over there a man and a woman are talking about something.

Perhaps it is not a coincidence that there are no web designers, copywriters, auditors or key accountant desk managers in children’s books. In the child's world, working life consists of bricklayers, farmers and nurses. People who help others, people whose work is utterly concrete and meaningful, people whose work has a distinct beginning and end.

As the children grow up, they learn that work is something different. This learning does not start at school, it starts at home. To fit into the working community, the child’s spontaneity and liveliness must be tamed early on. The first adaptation to work is usually related to noise. The child must learn to be quiet on command. It is also vital that the child learns early in life to eat and sleep at command. This is largely what parenthood is about. In school, it becomes more crucial to sit still on command, to only talk when talking is allowed, to read, count, run, sing, create according to the teacher’s instructions. A child who learns all this is well-prepared for work.

Naturally, it is a long and hard fight to teach the spirited little creature all these things. But the child eventually gives in. It becomes pliable, easy to manage, clever and enthusiastic. It is not uncommon that the child begins seeking external restrictions. Without these restrictions the child feels worried. Sometimes, it can even create its own restrictions. Once the long working life is over and the child comes out the other side, as a pensioner, it often doesn’t know what to do with itself. The world that initially lay open and full of potential is now closed. The child nervously seeks out bright rooms where people do carpentry and sewing – almost like work, but not quite. It sedates itself with TV and various substances. After lifelong subordination to the will of others it is virtually impossible to rediscover free will.

In this long process – which we call life – the notion of work changes radically. Although it is seldom perceived in this way, the time in the office feels relatively safe. One is “working”. One does what one is told. This behaviour is accepted. But is it work? Cleaners move around here and there, carefully separated from the

mind-workers they are supposed to clean up after. They are working. Their work is tangible. They are also aware that they are working. They would never dream of identifying themselves with their work. But what actually takes place on these screens around us? What is the blue light that shines into the night? What is said in those meetings? What is that presentation about?

Perhaps we are wise not to think too much about it. After all, if we have a job we should be happy. And if we have a job with an ergonomic office chair and free coffee, we are among the privileged.

There was a time when work was something that was sold by one party to another. That was before. Today, work is a gift, something employers give to the work-thirsting people. It is a beautiful gift. Work gives meaning to life, they say.

And yet, it is such a hard concept to grasp. What is the product? What is the service? Is it needed? What would happen if it didn’t exist?

It doesn’t matter. We have to work, or we don’t get any wages. We can’t afford not to work. Even though we get richer and richer every year. We’ve ensured this by basing our economy on growth. But this growth has no real value if it cannot be distributed. And how do we distribute it? With work. With wages, tax on wages, and a bit of tax on the consumption that work generates. That is the main purpose of work. And it is evident in how we speak of work. We don’t work to “generate growth”. Growth is generated by other things. But we want growth. Growth is good, because growth creates jobs. Jobs that could just as well be kept back, but which are given to us, as an act of benevolence, so that we can take part in working life, be a part of the community, be included in the overall context.

It’s time to leave now, perhaps we’ll make it to the bus at 5.34 pm if we take the shortcut through the snow again. In the canteen the cleaner sits down on a chair, he looks tired and devastated. We take forbidden pleasure in at least not being in his shoes. We should be grateful, after all, there are people who are far worse off. And tonight there’s a new episode of that TV series. For a short while, we can look at the cosy lighting and the Christmas decorations without fear, with warmth, almost like when we were children. We do our best – for the home, for our holidays, for the kids. The fantasy that we are all updated versions of bricklayers, nurses and farmers is comforting. Perhaps there is some meaning to that job, even if it is hard to see? Perhaps we are living inside a large, luminous ant hill where all the fragments of labour, even those we experience to be the most pointless, together form a magnificent whole? Perhaps all this is needed for the airplanes to fly, the medicine to work and the tap water to flow?

Or perhaps not.

Roland Paulsen

Author and Doctor of Sociology

ULF LUNDIN

Born 1965. Lives in Stockholm, Sweden.

EDUCATION:

1995-1997 MFA, Högskolan för fotografi och film, Göteborg, Sweden

1990-1993 BFA, Fotohögskolan, Göteborg, Sweden

Zhou Hanshun www.zhouhanshun.com

Artist’s Statement:

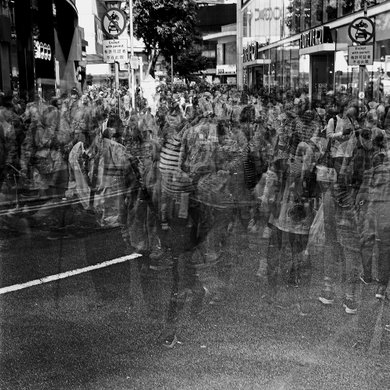

Frenetic City

To say life moves fast in a city is an understatement. From daily commuting to eating lunches to causalconversations, people go through life in an uncompromising and chaotic pace. Everyone from the rich to the poor, the fortunate and the unfortunate, the young and the old – moves through the city like a chaotic mass, overcoming and absorbing anything in their path. Time in the city seem to flow quick-er, memories in the city tend to fade away faster. Nothing seems to stand still in a city.A UN report suggested that by 2050, the world's population would reach 10 billion, with three-quarters of humanity living in our already swelling cities.Hong Kong is one of the most densely populated areas in the world, with a population of over 7 million but less than 25% of its land developed. When I first arrived in Hong Kong, I was immediately confronted by a society that is in fierce competition for physical and mental space.

This project is attempt to capture the unforgiving way of life in this city.

ZHOU HANSHUN

Born and raised in Singapore. Currently living & working in Hong Kong. Visual Storyteller, Photographer, Printmaker and Art Director.

Education

1993 – 1996, Diploma in Graphic Design (Photography Major),

Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, Singapore

1998 – 1999, Bachelor of Design, RMIT University, Australia

2009 – 2010, Certificate in Printmaking,

Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, Singapore